- The Behavioral Scientist

- Posts

- The Behavioral State Model (Part 4)

The Behavioral State Model (Part 4)

Social Status & Situation.

All behaviors, even solitary ones, are social.

We humans are social creatures. All our behaviors, even those performed in private, are influenced by social pressures.

Because we rely on others for our survival and success, a large portion of our cognition is dedicated to understanding and becoming valuable within our social scene.

Consider how quickly fashion trends change: one week, a particular shoe is the must-have item, and just a few months later, another brand takes its place.

In the realm of ideas, trends move even faster. A new video trend pops up, a new word gets invented, a new influencer becomes all the rage, and so on. Staying up-to-date with these developments is essential for signaling group identity and status.

While the cognitively demanding nature of social norms is most obvious in the young, the same thing is true, to varying degrees, for everyone.

We all belong to a community and social scene, and each social scene has things it values and things it despises. Understanding these things and behaving in-line with them is something that we all do subconsciously. This drive often leads us to conform to group norms, even at the expense of our personal beliefs or comfort.

This is even true of large decisions like what career to pursue.

If you took someone who was born in the woods and had never been exposed to any culture, and then asked them if they would like to spend all day with people who have contagious diseases and perform surgeries on them, they would probably respond with confusion and horror. The truth is, the activities associated with being a doctor are not inherently glamorous. Without the status that our social groups assign to this role, it’s exceedingly unlikely that many people would choose this profession.

The same thing is true with sports.

Almost no one curls. It’s not seen as high status or cool. Thus, very few people engage in this activity.

If it were seen as valuable, people’s behavior would be quite different.

Consider the case of a teenager, Alex, who is passionate about the arts but feels compelled to pursue a career in tech due to social and parental expectations. This sort of internal conflict between personal interests and societal pressures illustrates the tug-of-war between individual and group desires.

Another example: the skateboarding community. In this social group, certain risky behaviors are glorified, which contrasts with the general societal focus on safety.

This is a nice illustration of how, in specific contexts, the norms of a niche group can overshadow broader group expectations.

Most of us naturally pick up the values of our immediate social network. These values determine what’s:

Valuable

High status

Strange

All else being equal, we will choose to do the behaviors that maximize our perceived value and status and minimize our perceived strangeness to our social groups.

Each of us is a member of many different social groups.

For example, a high schooler may be a member of the track and field social group while at school, and then log into their computer and engage with their photography fanatics club on Reddit after getting home.

That same high schooler might even be a part of multiple social groups while at school. They have their track and field crew they spend most of their time with, but also the choir group that they spend their time with after classes each spring.

Social groups can also be classified by their level of “magnification”. Some groups are small and specific while others are broad.

For example, that same hypothetical high schooler is also a member of their family’s social group, their high-school’s social group, their town’s social group, their state’s social group, and the United States’ social group.

While some of these groups overlap, others do not. And while some of these groups are at the same level of magnification, others are nested within one another, like Russian Dolls.

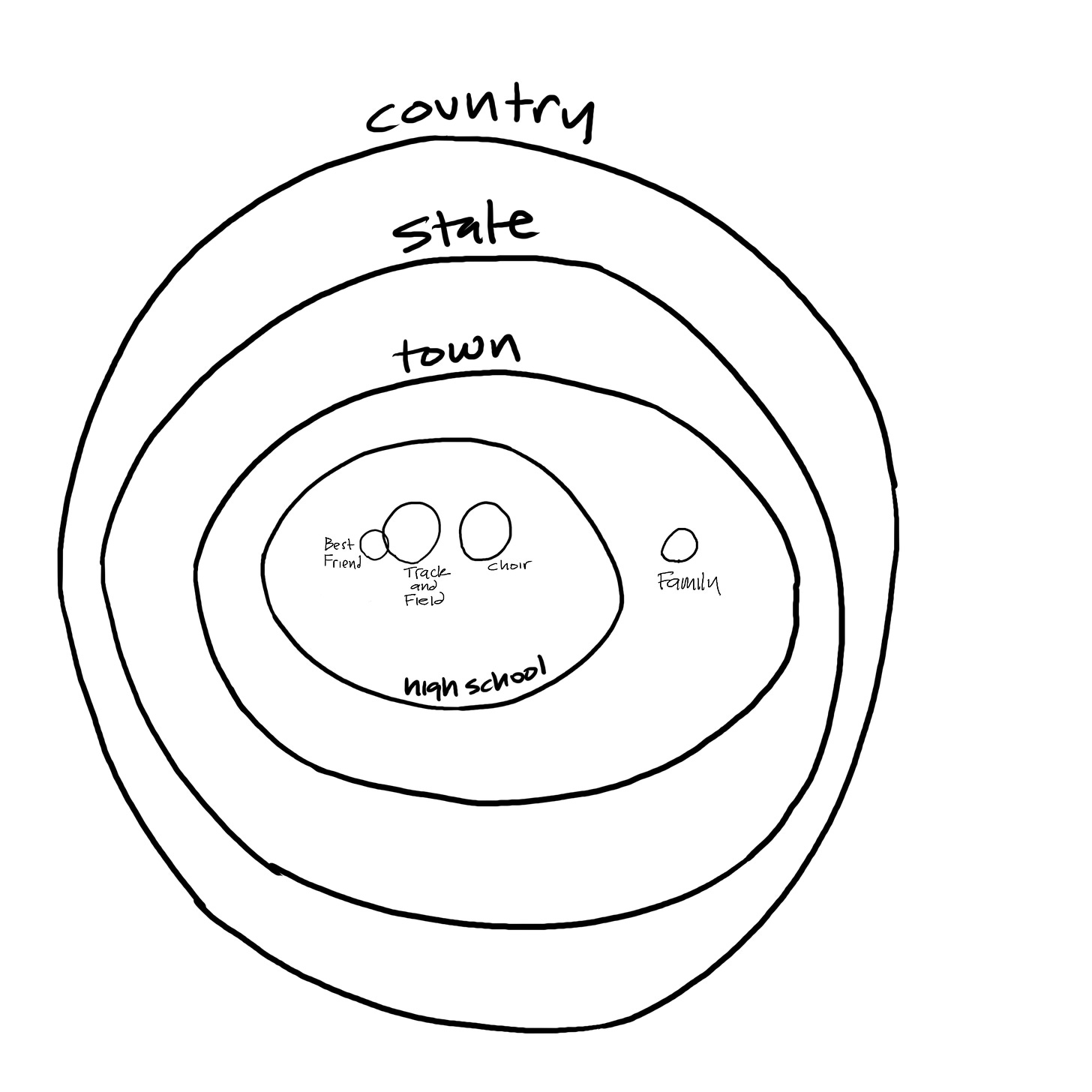

If we were to draw out a graphical representation, it would look something like this:

As you can see, this person belongs to eight different social groups:

Best friend(s)

Track and field

Choir

Family

High school

Town

State

Country

These groups can be ordered in terms of their “level”. Groups at the lower levels are smaller.

Level 1:

Best friend(s)

Family

Level 2:

Track and field

Choir

Level 3:

High school

Level 4:

Town

Level 5:

State

Level 6:

Country

As you may have noticed, groups are nested in various ways. For example, the best friend, track and field, and choir groups are all nested within the larger high school group. The family group, while at the same level of the best friend group, is not. However, all these groups are nested in the town group.

You may have also noticed that the best friend group overlaps with the track and field group. This is because some members of the best friend group are also members of the track and field team.

Why does this matter?

It matters because the influence of social groups is not equal.

You are going to care what people from your high school think more than what people from another high school think.

In addition, you probably care more about what your family thinks than what some random group of people who also live in your state think.

The smallest groups we’re closest to are often the most influential.

However, this isn’t always the case.

Ranking influence

Ranking the influence of social groups is a daunting task.

However, generally, the more we identify with a group the more influence it will have on us.

This is called “Ingroup Bias”.

And, in general, it’s much easier to identify with smaller groups. The more niche a group is, the more we can have in common with it, and the stronger our attachment and emotional bond with it will be.

Thus, the smaller groups that we are a part of will tend to have more influence on us.

This is why, when trying to understand someone’s behavior, it’s important to look at the small social groups they spend their time with.

Size matters

However, smaller groups are not always the most influential. Large groups can apply a tremendous amount of social pressure.

For example, in the case of national or cultural identity, the values and norms set by a large group like a country can be incredibly influential. The expectations of our society regarding behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs can shape our actions in profound ways. National holidays, cultural practices, and even laws are examples of how large social groups exert their influence over us as individuals.

Also, the media significantly amplifies the values and norms of larger social groups. We are constantly exposed to dominant cultural and societal norms through things like TV and social media. This constant exposure can reinforce certain behaviors and discourage others, effectively shaping our actions even when we're not directly interacting with members of these groups.

To put it simply: the balance between the influence of small, intimate social groups and large, societal ones is complex. While we may feel a stronger personal connection to smaller groups, the broader societal context cannot be ignored. This becomes particularly evident when the norms of a small group conflict with those of the larger society. In these situations, predicting which set of values is going to shape behavior can become a nearly impossible task.

So what does this mean for behavior change?

It means a few things:

To understand why a person is behaving the way they are, it’s important to understand their social standing.

What social groups do they belong to?

What are the smallest, most intimate groups they’re a member of?

What are the values of those groups?

Which social group is dominant in the relevant context?

Which media does this person/group consume?

What messages are the media promoting, and what behaviors or attitudes are they encouraging?

Does this person consume any media sources specific to this behavioral domain? If so, what are they and what are their messages?

P.S. If you want to learn my research-backed point of view on personal behavior change, check out my book. Please leave a review if you like it.

P.P.S. If you need to remote talent, check out my company.

P.P.P.S. I’m running a pilot program where I do an in-depth personality assessment of you and provide guidance on: 1) your strengths 2) your critical weaknesses 3) your relationships 4) which types of activities would best accomplish your goals. This pilot is not cheap, and I’m only taking 5 people. If you’re interested, please respond to this email to reserve a spot.